Our analysis revealed that 20%-40% of physicians targeted for a pharmaceutical product see very few patients they feel are ‘ideal candidates’ for the product. This is despite seeing numerous patients who have the condition.

Moreover, there are often numerous physicians with relatively low prescription volume who happen to see a high proportion of patients who are strong candidates for a medication that pharma companies often overlook.

Field reps see the issue first hand. Just about every rep can relay experiences of doctors whose love for the drug far exceeds their Rx habits.

Starting with the Patient

Addressing this issue is straightforward: target doctors who see patients who are strong candidates for the drug. That may sound like it’s easier said than done, but in the primary care market where the issue is most pronounced, it’s not nearly as daunting a task as it seems.

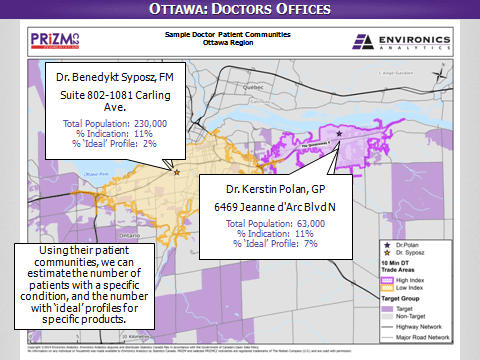

Primary care physicians generally draw the vast majority of their patients from within a certain distance of their offices, usually a 10-minute travel time (though this differs based on population density). Using the address of a physician’s office and the travel time metric, it’s easy to create a border of a physician’s ‘trade area’ or ‘patient community’ in much the same way we do so for retail pharmacies or grocery retail locations.

Looking at the 6-digit postal codes that compose the ‘patient community’, we can identify the types of patients who reside in each community. This is possible through Statistics Canada census data, specifically the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). The CCHS captures numerous aspects of a person’s health profile including condition/disease prevalence and insurance coverage. It’s possible to generate a very detailed profile of the patients in a given ‘patient community’ by combining CCHS data with other demographic and psychographic information from the census and other data sources. (Looking at these datasets together was how we produced the analysis described above).

This level of information provides pharmaceutical companies with a lot more options for physician targeting and product promotion. What’s more, this level of detail is not subject of the same black-outs that exist for physician level data in BC, MB, and NL.

In addition to being able to identify which physicians have the best ability to deliver patients for a particular drug, knowing who these patients are in terms of needs, co-morbidities, media habits, education, and socio-economic status allows for tailored patient outreach and marketing.

An Industry Not Used to Sales and Marketing Innovation

Sales and marketing people from outside our industry are often shocked to learn pharmaceutical has not discovered and adopted this practice. However, this is pharmaceutical, not flavoured soft drinks or quick serve restaurants, where understanding the end user is paramount.

In pharmaceutical, the pace is conservative and adopting this type of approach requires discipline, namely, identifying a target/strong candidate patient for a drug product (just as Coca-Cola or McDonald’s identify a target consumer). The barrier is that it is generally foreign to pharmaceutical product managers.

In the pharmaceutical world, product managers, usually under the coaching of senior people who were themselves product managers in a different era, usually define their market as ALL the patients who suffer from the condition for which their product is indicated. (Coke moved beyond defining their market as ‘anyone with a thirst’ decades ago).

Identifying an ideal candidate patient for a specific drug is a leap for most drug makers because of the fear of leaving behind numerous patients who may not be ‘ideal’ but could still benefit from the drug. Increasingly what we see is that the opposite is true.

Pitfalls of Poor Patient Selection

By not defining who the strong candidate patient is for a drug, physicians inevitably select weak candidates for the drug (often late line patients who have failed on multiple other therapies). These weak patient candidates then don’t perform all that well on the drug, often for reasons that have nothing to do with the quality of the molecule. Yet, this poor performance is what doctors often use as the basis for their opinion of the drug. It’s these negative perceptions that keep the drug out of the hands of patients who would likely perform extremely well with it.

When drug makers can paint a clear picture of a strong candidate for their drug, physicians can select patients with the best chance of success. The positive experience that goes with seeing patients perform well on a drug gives the physician the confidence to use it with an increasingly broad pool of patients.

Opportunities in Patient Marketing

KNOWING your drug’s ideal patient (who they are, where to find them, what they value) creates a lot more options for highly targeted patient marketing. This includes developing broad strategies such as creating the type of brand personality for your drug that connects with your most important patients that motivates them to advocate for it with physicians and payers. It also includes equally important marketing tactics such as in-office patient materials, sample distribution, and out of home messaging. All of which are far more efficient when you have a strong sense of who your customer is and where to find them.

Doing More with Less

Some pharmaceutical companies have figured this out. Usually it’s the smaller ones who are a more agile and have not had the distraction of restructuring that has been common in the larger pharmas.

In the post-restructuring era of pharmaceutical where brand and sales teams are challenged to ‘do more with less’, revisiting how the market is defined may be a good place to start.