COVID-19 Vaccines: Not As Divisive As You Might Think

Posted on: Friday Jan 15th 2021

Article by: Vijay Wadhawan

Amid all this hand-wringing, where does the public stand? Mostly on the side of getting vaccinated, according to our recent survey.

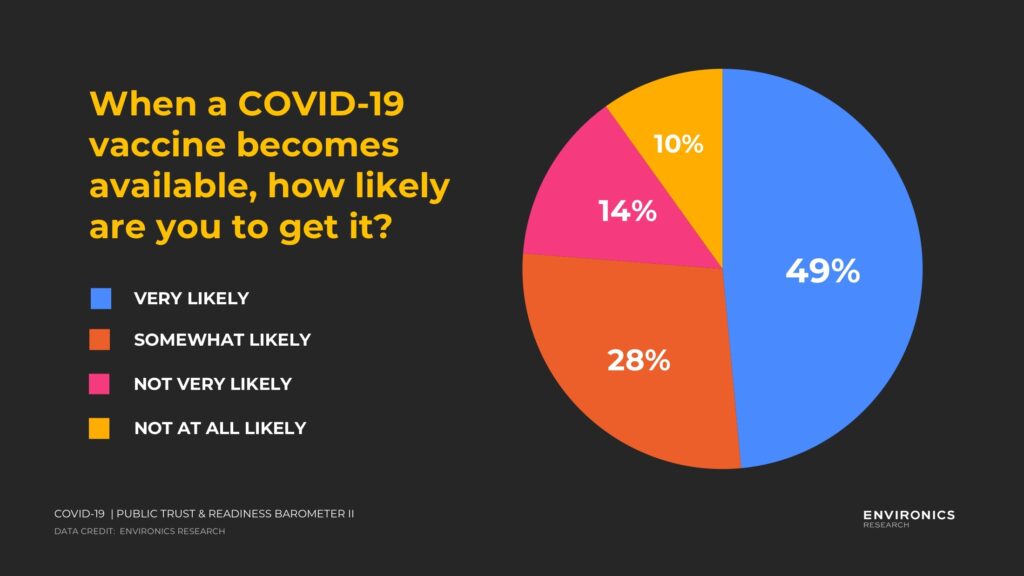

In September 2020, we asked a robust sample of Canadians how likely they are to get a COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available.

About half of Canadians (49%) said they were very likely to get the vaccine – meaning they probably will do so – while another almost three in ten (28%) are somewhat likely to do so. In this latter group, some might get vaccinated on their own, some might do so with a little convincing, and some may opt out. A little over one in ten say they are not very likely to get the vaccine, and only one in ten Canadians are adamantly not at all likely to get it.

Interestingly, Canadians across much of the political spectrum feel similarly; the proportion that are very or somewhat likely to get the vaccine ranges from 70% for Conservative supporters to 84% for Liberal supporters, with NDP and Green supporters falling in between (77% and 74%, respectively). Those least likely to plan on getting vaccinated are supporters of the Bloc Québécois and of the People’s Party of Canada, and those who say they don’t vote at all – about six in ten each.

If half of Canadians are already fully on board, what will it take to firm up the commitment of some of those who are inclined toward vaccination, but not totally sure? How do we achieve that 60% threshold?

From this perspective, it appears that Canada has pretty good prospects of achieving population immunity over the coming months. According to Dr. David Naylor of the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force, a vaccination rate of about 60% would be sufficient to “blunt dramatically” the spread of the virus.

If half of Canadians are already fully on board, what will it take to firm up the commitment of some of those who are inclined toward vaccination, but not totally sure? How do we achieve that 60% threshold? By tailoring messages to align with people’s underlying values and motivations, the chances of connecting with them in a persuasive way increase considerably.

The values of those in the ‘least likely’ crowd suggest a group that is skeptical, impulsive and inclined to think they can handle the virus themselves – “we don’t need vaccinations.” This group won’t be easy to convince.

Turn to the three in ten Canadians who are already somewhat likely to accept a vaccine, however, and you have something to work with. Values research suggests that these Canadians are above average in their desire to be part of a larger group with whom they can share activities and experiences. In the case of the pandemic, this attraction to the collective may create an opening for messaging along the lines of: “Join millions of Canadians in getting vaccinated and stopping this deadly virus.”

While some Canadians dismiss advertising messages regardless of the source, those who express moderate interest in being vaccinated are receptive to advertising and mass communication. An effective ad from a credible source has a good chance of reaching them with a message about vaccination.

Finally, this group is motivated partly by status and prestige – meaning that, for them, a proof of vaccination card (or vaccine “passport”) could become a kind of status symbol that would make vaccination more appealing.

Despite warnings of widespread vaccination hesitancy, Canada appears well-positioned to achieve population immunity. A small minority of the public are likely to refuse; but for those who just need reminding and reassurance, values-based communications can cut through the noise and connect.

Tags:

More Articles

Thought Leaders

Generosity in 2025: How Giving Is Evolving This GivingTuesday

12/02/25

Annika Jagmohan

Industry Trends

Do Canadians Trust AI in Healthcare? It Depends.

11/20/25

Vijay Wadhawan

Industry Trends

How Advisors and Clients are Responding to the 2025 U.S. Tariffs

11/12/25

Arzum Gulercan