Why is trust so important in healthcare?

Posted on: Friday Oct 20th 2023

Article by: Vijay Wadhawan

ARTICLE

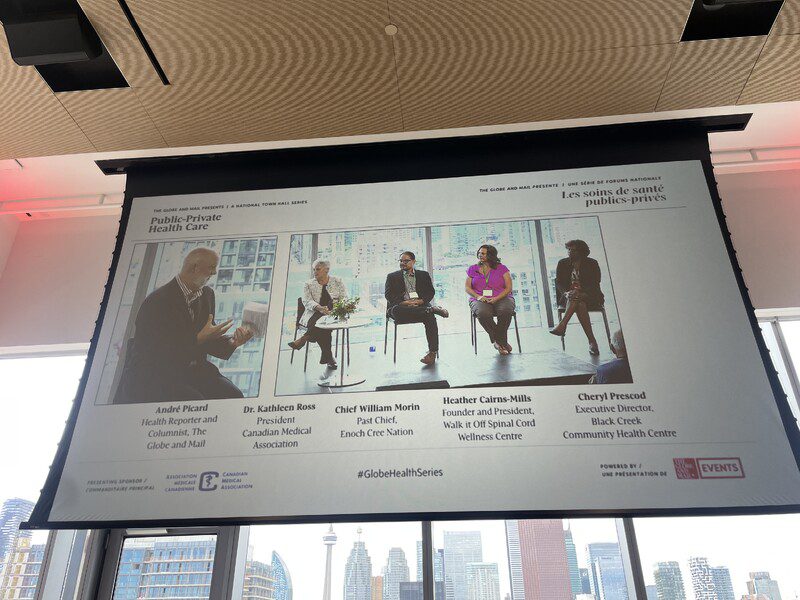

Earlier in September, I attended the first of a series of Canadian Medical Association consultations in partnership with The Globe and Mail Events that focused on the role, if any, private care should play in Canada’s publicly funded healthcare system. The event featured speakers and panels that included patient advocates, healthcare professionals, and digital health innovators. A myriad of topics were discussed, from efficiency and quality to access, equity and innovation.

As the conversations unfolded, I noticed there was one vital aspect of healthcare that was less often named but present in nearly every session: trust. Regardless of the model they were advocating, speakers consistently made the case – sometimes explicitly, sometimes indirectly – for the importance of building trust in healthcare systems.

Picture from Canadian Medical Association consultations in partnership with The Globe and Mail Events

Public versus private: different drivers of trust

Advocates of publicly funded healthcare (where the role of private services is limited) contended that, if resources are used appropriately, the system can deliver more equitable access, fostering a sense of fairness and ultimately trust – perhaps not only in healthcare but in society and its institutions. On the other hand, those in favour of a larger role in private healthcare often pointed to the efficiency, choice, and innovation that competition can drive, arguing that these factors could improve patient trust by offering a more personalized approach to care.

Efficiency and access

When discussing the efficiency of private healthcare models, many speakers noted that reduced wait times and quick access to medical care are key benefits. These are not just logistical advantages; when a system is prompt and responsive, it instills confidence in users. As in any well-run operation, small signals of competence (clear communication, orderly workspaces) suggest that core functions are probably well-handled, too. Meanwhile, public healthcare advocates argued that universal access creates a foundational level of trust among all citizens – regardless of their financial means – and that quicker access to care can be achieved through improved use of existing resources: better leveraging the capabilities of nurses and pharmacists, for example, and smoothing the entry of internationally trained physicians into health systems.

Quality

Quality of care tends to be a universal priority. Proponents of a greater role for private providers often argue that competition drives facilities to offer better-quality services, which in turn can improve patients’ trust in the care they receive. Public-system advocates argue that the standardized guidelines and protocols of a strong public system safeguard quality for all, fostering a generalized sense of trust in care that’s not limited to any specific clinic or brand.

Data security and innovation

Electronic health records, telehealth, and other digital tools play an increasingly central role in healthcare, across delivery models. While these tools offer clear benefits – not only streamlining services and boosting efficiency but also supporting innovation – they also raise questions about data privacy and security. For both public and private entities, robust security measures and privacy protocols are essential to maintaining patient trust.

Equity and social trust

Public healthcare supporters at the CMA event emphasized how a universal system can help bridge societal divides and contribute to social cohesion – effectively increasing collective trust. In contrast, proponents of private healthcare insisted that choice and individual agency in selecting healthcare services can also lead to trust, albeit at the individual level.

Why is trust so important – and what factors help to build it?

Although the CMA consultation was not designed to focus on this theme, I was struck by how often the idea of trust came up in the event’s wide-ranging dialogue. I see two reasons. First, trust is a sign of healthy system: only a safe, effective, humane healthcare system will earn the trust of the people who use it. Second, trust is a characteristic that can help to make health systems more effective. When patients trust their health system, it stands to reason that they will be more likely to use it, be more receptive to the guidance of care providers, and perhaps even be more inclined to access upstream support such as primary care (“It’s worth a try…”) instead of waiting until their condition is so serious that they’re forced to seek help.

But while the value of trust may be universally recognized, there are different ways to promote that trust – and they go beyond the differences implied by public versus private delivery. Healthcare providers will be most effective in building trust if they understand the people they serve not only from a demographic and clinical point of view but also in terms of their perspectives and health values. By understanding the attitudes, values, and beliefs of different groups within the populations they serve, healthcare organizations and policymakers can tailor strategies to address specific concerns and dismantle barriers of mistrust.

For example, building partnerships with community leaders and influencers can help experts disseminate scientifically accurate information in ways that are approachable and culturally sensitive. Similarly, thoughtfully tailored programs to increase health literacy, especially among those in equity-deserving groups, can equip people to advocate for their own health more effectively – ultimately getting more benefit out of the system, and ideally creating a positive feedback loop of dialogue, mutual understanding, trust, and quality care. Finally, policies that demonstrate transparency, equity, and inclusivity can significantly boost public trust – especially among people whose values are less deferential to authority (who are less likely to accept “doctor’s orders” on faith).

When the healthcare system is viewed as a reliable partner that respects and understands the complexities of its community’s social fabric, it is more likely to be successful in building relationships of trust. That trust can in turn enhance care providers’ ability to support patients in achieving the best possible health outcomes, whatever the mechanics of the system they’re working in.